In the age of low-code tools and AI-assisted prototyping platforms, it’s easy to wonder: Is there still a place for paper prototyping in product discovery?

Modern tools like Lovable and Cursor can produce high-fidelity, interactive prototypes in minutes. They’re especially helpful for remote collaboration, quick iteration, and presenting something that looks ready for production. For many product teams, this shift has lowered the barrier to testing, enabling more frequent and low-cost experiments at greater scale.

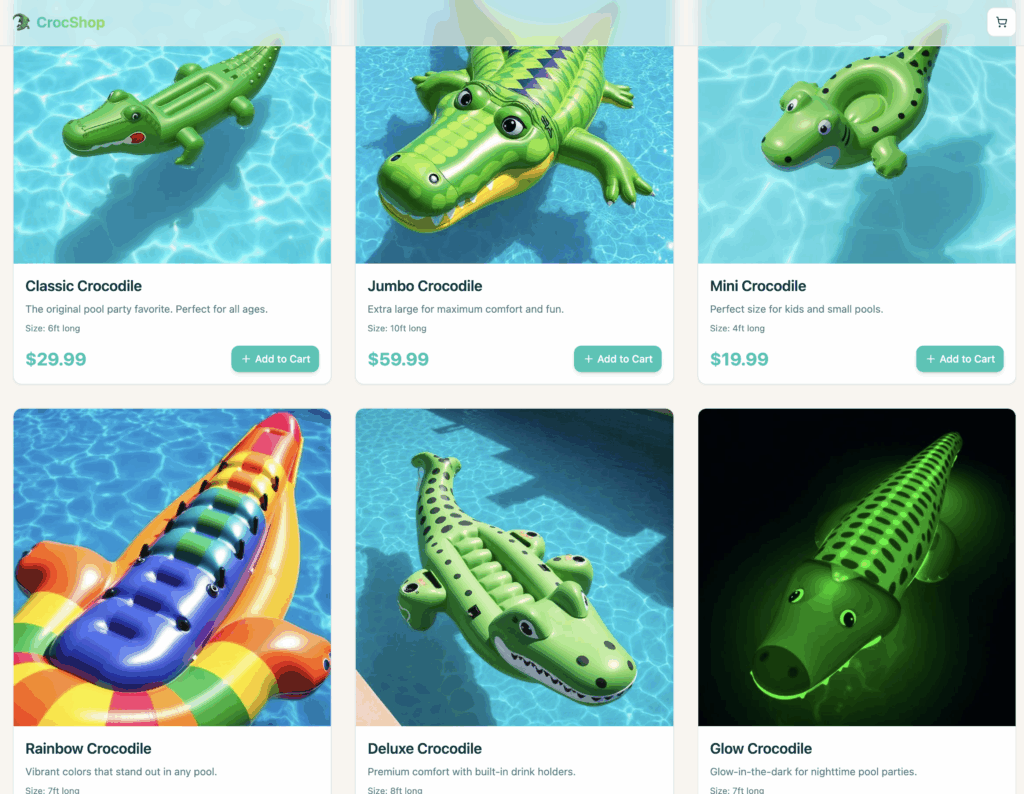

This opens up a playground of possibilities. A participant of one of my product management classes recently asked “can you also use Lovable to create a webshop for inflatable crocodiles?” As we found out on the spot after typing 2-3 sentences in Lovable: sure you can (see below)!

But this convenience comes with risks.

In my work with product professionals, I often see the line between prototype and product begin to blur. When something looks polished, the temptation is to launch it, even if it hasn’t been validated as desirable (people want it), viable (it beneficial to the organisation building it), or feasible (it can be built with reasonable effort). Discovery becomes a checkbox. We slip into premature certainty. And before long, we’re back in a feature factory, obsessing over output (features, milestones, etc.) instead of outcomes (this new product/service enables people to solve an actual problem or get a meaningful job done).

That’s where paper prototyping still shines. It’s fast, disposable, and low-cost. It makes it easy to focus on the problem instead of getting distracted by the polish of a solution. Paper invites critique because it doesn’t look finished. It fosters open-ended conversations, especially in co-located workshops where body language, energy, and spontaneous insights matter. And because it’s so lightweight, it’s easier to throw away, which is exactly what you want when you discover that an idea doesn’t hold up.

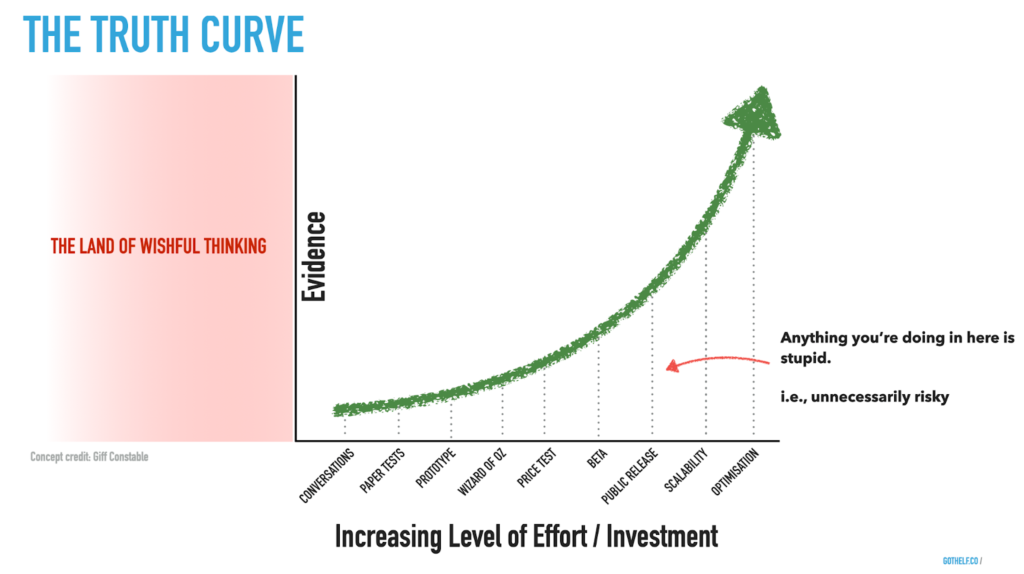

Of course, digital tools offer clear advantages, especially when you’re refining flows, working remotely, or need fidelity to test interaction details. The point is this: the best method is the one that gives you reliable answers with an appropriate amount of effort and acceptable levels of risk. This point is illustrated beautifully in Giff Constable’s Truth Curve (see below).

Early in discovery, when you have little evidence, the cost of learning should be low. Think sketches, interviews, or simple landing pages. As your confidence grows due to increased evidence, it makes sense to invest in higher-fidelity prototypes or live experiments. The Truth Curve reminds us to match the fidelity of the method to the certainty of our assumptions, so we don’t waste time validating ideas that were never worth building.

The job of a product manager or designer is not to fall in love with fancy tools for advanced product discovery, but to stay close to the following questions: “What are we trying to learn? What assumptions are we testing? What is the fastest way to reduce uncertainty without overcommitting?”

Tools don’t replace the messy but essential work of discovery. They augment it. The art of product management lies not in what you build, but in how you learn. Whether with pen and paper or pixels and code, the goal is the same: question, explore, adapt, and build what truly matters.